| *featured, #project, #ruby | |||

Entry-level CompilerTheory Behind Building a Markdown to HTML Compiler |

|||

markie

markie

A compiler’s job is to translate one language into another. We use them in computer programming to transform the high-level languages that humans can read and write into something that computers understand.

For example, our source language might be C, which we can write, and our target language could be assembly, which our computers can run. Without a compiler, (or an assembler in the case that our target language is assembly), we would have to work with computer instruction sequences that lack the expressiveness that we’re used to in modern-day software development.

I won’t pretend to speak with any authority on compilers, but what I would like to do is share the baby steps I’ve taken into the fray by introducing the markdown to HTML compiler that I’m currently working on in Ruby.

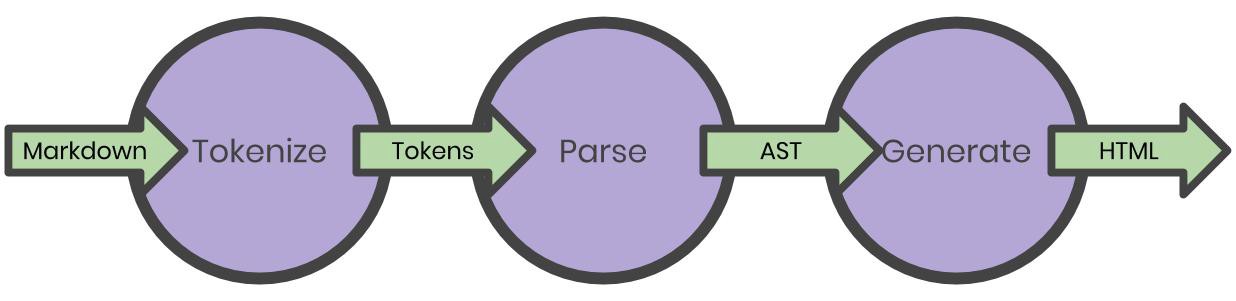

Of the most common compiler architectures that I’ve researched, at their core, they all seemed to have a few things in common: tokenizing, parsing, and target code emission.

Tokenizing is the act of scanning the source code character-by-character, and producing a list of tokens which contain metadata about the source code.

Parsing takes that list of tokens and creates a tree structure, specifically an abstract syntax tree. This tree represents the hierarchical structure of our source code and obfuscates any details about the source language’s syntax. It does this by following a set of rules know as the *grammar *of the language.

Finally, code emission turns the abstract syntax tree into the target language by walking the tree branch-by-branch, node-by-node.

Lexical Analysis

Also know as scanning or lexing, this first step in our compiler is to turn the characters of our markdown into tokens.

What’s a Token?

You can think of a token as a character, or group of characters, with metadata or context related to what those characters represent in our source language. “Character” in our case means the literal character strings that are used to make up the code that we write.

Let’s say we write some source code:

a

It’s very simple, it just contains the character a. If we were to tokenize our code, we might get something like:

Tokenizer.scan("a")

=> #<type: :text, value: "a">

In this example, we’ve captured some metadata about the “code” that we wrote and began to attribute some context , :text, to it.

Another example might be this source code:

_a_

If we tokenize this source code, we end up with:

Tokenizer.scan("_a_")

=> [

#<type: :underscore, value: "_">

#<type: :text, value: "a">

#<type: :underscore, value: "_">

]

This time, we have more than just text; :underscore is a significant piece of syntactical information in our source language, and therefore we make sure to write a rule so that our tokenizer can capture it.

Why Tokenize?

Having a stream of tokens, where you once had a stream of characters, allows our next step, the parsing, to do it’s job more efficiently. Not only that, during the scanning process, we can start to look out for syntax issues, (like encountering a character that our language doesn’t have a definition for). Tokenizing is only one step under the umbrella of lexical analysis. This analysis can be more robust for real programming languages, but for markdown in particular, tokenizing is a pretty straightforward process:

markdown = "[Markie]([https://github.com/Thomascountz/markie](https://github.com/Thomascountz/markie)) isn't _the_ best, but it's fun!"

tokens = Tokenizer.scan(markdown)

=> [

#<type: :open_square_bracket, value: "[">,

#<type: :text, value: "Markie">,

#<type: :close_square_bracket, value: "]">,

#<type: :open_parenthesis, value: "(">,

#<type: :text, value: "[https://github.com/Thomascountz/markie](https://github.com/Thomascountz/markie)">,

#<type: :close_parenthesis, value: ")">,

#<type: :text, value: " isn't ">,

#<type: :underscore, value: "_">,

#<type: :text, value: "the">,

#<type: :underscore, value: "_">,

#<type: :text, value: " best, but it's fun!">,

#<type: :eof, value: "">

]

Real-world Example: Ruby & Ripper

Even though Ruby isn’t technically compiled, (it’s interpreted), a lot of the same compiling steps apply. Ruby ships with a tool called Ripper that allows us to peek into, and interact with, the interpretation process of the language itself. Let’s take a look at the lexical analysis of Ruby using Ripper.tokenize() and Ripper.lex()

require 'ripper'

source_code = <<CODE

def plus_two(x)

x + 2

end

CODE

Ripper.tokenize(source_code)

=> ["def", " ", "plus_two", "(", "x", ")", "\n", " ", "x", " ", "+", " ", "2", "\n", "end", "\n"]

In the example above, we see that Ripper.tokenize() returns an array of strings that represent the value of each token that it scanned. It was able to distinguish keywords like def, (, and end from methods like + and variables like x.

We can take an even deeper look with Ripper.lex()

require 'ripper'

source_code = <<CODE

def plus_two(x)

x + 2

end

CODE

Ripper.lex(source_code)

=> [[[1, 0], :on_kw, "def", EXPR_FNAME],

[[1, 3], :on_sp, " ", EXPR_FNAME],

[[1, 4], :on_ident, "plus_two", EXPR_ENDFN],

[[1, 12], :on_lparen, "(", EXPR_BEG|EXPR_LABEL],

[[1, 13], :on_ident, "x", EXPR_ARG],

[[1, 14], :on_rparen, ")", EXPR_ENDFN],

[[1, 15], :on_ignored_nl, "\n", EXPR_BEG],

[[2, 0], :on_sp, " ", EXPR_BEG],

[[2, 2], :on_ident, "x", EXPR_END|EXPR_LABEL],

[[2, 3], :on_sp, " ", EXPR_END|EXPR_LABEL],

[[2, 4], :on_op, "+", EXPR_BEG],

[[2, 5], :on_sp, " ", EXPR_BEG],

[[2, 6], :on_int, "2", EXPR_END],

[[2, 7], :on_nl, "\n", EXPR_BEG],

[[3, 0], :on_kw, "end", EXPR_END],

[[3, 3], :on_nl, "\n", EXPR_BEG]]

In this example, Ripper.lex() returned an array of arrays containing some metadata about each token in the format of:

[[lineno, column], type, token, state]

Parsing

After completing lexical analysis, we end up with a list of tokens. These tokens are then used by the parser to create an abstract syntax tree.

What’s an Abstract Syntax Tree?

Also called an AST for short, it’s a tree data structure of branches and leaf nodes that encodes the structure of our source code sans any of the syntax, (that’s what makes it abstract.)

I learned more about ASTs from Vaidehi Joshi’s BaseCS article Leveling up One’s Parsing Game with ASTs, and highly recommend your read it for an in depth look at this data structure and how it’s used in parsers.

For parsing markdown specifically, markie builds an abstract syntax tree by translating certain groups of tokens into nodes on a tree. These nodes then define what those tokens represent in the context of a markup language.

Before we unpack that, let’s expand on one of our earlier examples:

source_code = "_a_"

tokens = Tokenizer.scan(source_code)

=> [

#<type: :underscore, value: "_">

#<type: :text, value: "a">

#<type: :underscore, value: "_">

]

Parser.parse(tokens)

=> {

"type": :body,

"children": [

{

"type": :paragraph,

"children": [

{

"type": :emphasis,

"value": "a"

}

]

}

]

}

In this example, our AST has a root node of type :body, which has a single child node, :paragraph, which also has a single child node, :emphasis, with a value of a.

Notice that our AST doesn’t contain any information about :underscore? That’s the part of this that makes it abstract. Our parser has turned the sequence of tokens with types :underscore, :text, :underscore, into a node of type :emphasis. This is because, in this flavor of markdown, :underscore, :text, :underscore, is the same an emphasis tag (<em>) in HTML surrounding that same text.

The nodes :body and :paragraph are generated to aid in the code emission step, next. These represent the <body> and <p> tags from our target language, HTML.

Let’s Take a Peek Ahead to See What’s Going On

HTML is tree-link by design. For example, if we have a HTML page like this:

<body>

<h1>Header</h1>

<p>Paragraph Text<a href="link_url">link_text</a> more text.</p>

</body>

We could represent the elements in a tree like this:

.Body

├── Header

│ └── Text("Header")

└── Paragraph

├── Text("Paragraph Text")

├── Link("link_url")

│ └── Text("link_text")

└── Text(" more text.")

Ultimately, that tree is what our parser aims to build out of the list of tokens from our tokenizer. If our parser is able to do that we can see how our code emission step, where we take the AST and generate HTML, should be relatively straightforward.

How Do We Generate the AST?

We saw earlier how our parser takes the tokens :underscore, :text, :underscore, and turns them into a node of type :emphasis, these translation rules that our parser follows is called the grammar.

At a high level, grammars in programming languages are similar to grammars in natural languages; they’re the rules that define the syntax of the language.

(Again, Vaidehi Joshi has us covered with her article called Grammatically Rooting Oneself with Parse Trees where she talks about how grammar applies to generating parse trees, a close cousin of abstract syntax trees.)

Let’s continue our example to enlighten our understanding. We’ll notate the :emphasis grammar like this:

Emphasis := <UNDERSCORE> <TEXT> <UNDERSCORE>

Whilst looking through our list of tokens, if we encounter this sequence,

Generally, in HTML, <em> sit inside of other tags, such as <p> or <span>, as well as many others. To keep things simple, let’s just start with <p>, therefore, it can be said that Emphasis nodes are child nodes of Paragraph nodes, so we can add that to our mapping as well:

Paragraph := Emphasis*

Emphasis := <UNDERSCORE> <TEXT> <UNDERSCORE>

Here, we borrow the Kleene Star, from it’s implementation in regular expressions, which here means “zero or more of the previous,” so in our case, a Paragraph node’s children are made up of zero or more Emphasis nodes.

Let’s add some more things that paragraphs can be made up of:

Paragraph := Emphasis*

| Bold*

| Text*

Emphasis := <UNDERSCORE> <TEXT> <UNDERSCORE>

Bold := <UNDERSCORE> <UNDERSCORE> <TEXT> <UNDERSCORE> <UNDERSCORE>

Text := <TEXT>

Here, we use | to indicate a logical OR, so now we have a Paragraph node that can be made up of zero or more Emphasis child nodes, or zero or more Bold child nodes,** or** zero or more Text child nodes. And now we know what sequence of tokens the Bold and Text nodes are made up from themselves.

However, this grammar isn’t quite correct. The way it’s written now, each Paragraph can have children made up of only one type of node. We need a way to represent AND/OR. i.e. a Paragraph can have children of zero or more Emphasis nodes, and/or zero or more Bold nodes, and/or zero or more Text nodes.

We can fix this by shimming in the concept of a Sentence, for example.

Paragraph := Sentence+ <NEWLINE> <NEWLINE>

Sentence := Emphasis*

| Bold*

| Text*

Emphasis := <UNDERSCORE> <TEXT> <UNDERSCORE>

Bold := <UNDERSCORE> <UNDERSCORE> <TEXT> <UNDERSCORE> <UNDERSCORE>

Text := <TEXT>

Here, we borrow the Kleene Plus, from it’s implementation in regular expressions, which here means “one or more of the previous.”

Now, Paragraph can have one or more Sentence which are made up of zero or more Emphasis, or Bold, or Text.

You may begin to see a pattern here. Each line is made up of an expression, followed by a definition. We started with Emphasis, which is a terminal in our grammar, meaning that it’s definition is based purely on tokens. Next, we added Paragraph, which is a non-terminal because it is defined in reference to other terminals *and/or *non-terminals. And we have the productions *which are the rules for turning *terminals into non-terminals, which for Paragraph is Emphasis* | Bold* | Text*.

What we just went through is a bastardization of the Backus-Naur form of defining context-free grammars. I’m not going to pretend to really know what those are, yet, but feel free to dig deeper!

Real-world Example: Ruby & RubyVM

Similar to before, even though Ruby is an interpreted language, it still goes though many of the same compilation steps, including the building of an abstract syntax tree. As of Ruby2.6, we can use RubyVM::AbstractSyntaxTree to interact with the virtual machine.

source_code = <<CODE

def plus_two(x)

x + 2

end

CODE

RubyVM::AbstractSyntaxTree.parse(source_code)

=> (SCOPE@1:0-3:3

tbl: []

args: nil

body:

(DEFN@1:0-3:3

mid: :add_two

body:

(SCOPE@1:0-3:3

tbl: [:x]

args:

(ARGS@1:12-1:13

pre_num: 1

pre_init: nil

opt: nil

first_post: nil

post_num: 0

post_init: nil

rest: nil

kw: nil

kwrest: nil

block: nil)

body:

(OPCALL@2:2-2:7 (LVAR@2:2-2:3 :x) :+

(ARRAY@2:6-2:7 (LIT@2:6-2:7 2) nil)))))

There is more data in RubyVM’s AST than our simple markdown example, but thanks to Ruby being so open, we can dig in and take a look around the RubyVM!

Target Code Emission

The last step for our markdown compiler is to generate HTML from the abstract syntax tree created by the parser. In our case, we traverse the tree top-down, left-to-right, and emit HTML fragments that are joined together in the end.

Continuing from our small markdown example from above:

source_code = "_a_"

tokens = Tokenizer.scan(source_code)

=> [

#<type: :underscore, value: "_">

#<type: :text, value: "a">

#<type: :underscore, value: "_">

]

Parser.parse(tokens)

=> {

"type": :body,

"children": [

{

"type": :paragraph,

"children": [

{

"type": :emphasis,

"value": "a"

}

]

}

]

}

First, we start at the :body node, traverse it’s child, :paragraph, then traverse it’s child: emphasis. Since we’re at a leaf node, we can begin walking back up the tree, generating fragments along the way.

First, the :emphasis node generates:

<em>a</em>

Then the :paragraph node:

<p><em>a</em></p>

And finally the :body:

<body><p><em>a</em></p></body>

This traversal strategy is call *post-order *traversal, and would normally be written like this:

def post_order(node)

if !node.nil?

post_order(node.left_child)

post_order(node.right_child)

puts node.value

end

end

However, this algorithm is for traversing binary trees, that is, trees where each node can have at most two children. For our abstract syntax tree, we can have many children, so instead, we can recursively map.

def post_order(node)

if !node.nil?

node.children.map do |child|

post_order(child)

end

puts node.value

end

end

We can do this because Ruby arrays are ordered, which means that we can depend on the order in which we placed elements into the array on remaining constant when we read from the array. We leverage this when building our list of tokens and our tree’s nodes by placing things in as we scan/parse them in order.

Conclusion

This article was to be written specifically about building a markdown compiler, but really it’s an overview of the theory behind the parser I’m currently working on called markie.

I originally tried to build a markdown-to-HTML gem in Ruby using only regex and String#gsub(), but that only got me so far.

Lucky for me, it turns out that real compiler architecture is battle tested and proven to be able to handle anything from turning markdown into HTML to turning C into Assembly. Instead of reinventing the wheel, I decided to stand on the shoulders of those giants who have come before me.

Ironically, markie itself is the reinvention of an old wheel; there are plenty of tools out there to do what I’m trying to get markie to do. However, the experience of learning about compilers and interpreters has been very exciting, and ultimately, markie is a jumping off point for many projects to come.

Thanks for reading! ❤️